Download the full article here

By

Ajit Patwardhan, MD1, MBA; Robin Winter-Sperry, MD2; Dannielle Heuer3; Stephen Valerio4; Urvashi Vashee5; Drilon Saliu, PharmD, MBA6; Greg Christopherson, PhD7; Irma Saliu, PharmD8; Kyle Kennedy9; Michelle Powell, PharmD10; Chris Brock, PharmD11 ; John B Pracyk, MD, PhD, MBA12; Joe Medicis, PharmD13

1 Physician – Surgeon, Medical Affairs Executive – Baxter International, Integra LifeSciences, NLT Spine, Paradigm Spine

2 President, Scientific Resilience; MAPS 2020 Co-Chair

3 Director WD Communications

4 Sr Director, Oncology Medical Training AstraZeneca

5 Global Scientific Training Merck & Co

6 Head, Global Medical Affairs, Clinical Development and HEOR, Connected Care Philips

7 VP, Medical Affairs Medline

8 National Director, Psychiatry MSLs, US Field Medical Allergan

9 VP, Customer Strategy – The Medical Affairs Company

10 Director, Filed Medical Excellence Astellas Medical Affairs Americas USA

11 Field Based Medical Affairs, Head, Respiratory GlaxoSmithKline

12 Integrated Leader, Medical Affairs, Pre-Clinical, & Clinical Research DePuy Synthes Spine, (J&J)

13 Director US Medical Affairs Callidiatas Therapeutics

ABSTRACT

The evolving role of Medical Sciences Liaisons (MSLs) was extensively discussed in multiple presentations and workshops at the March 2020 Medical Affairs Professional Society (MAPS) Global Annual Meeting in Miami, Florida. Executive leaders with domain expertise in building and managing Field Medical teams shared their experience and views on the value proposition of these roles and how a changing healthcare and industry landscape is influencing differentiation of and new opportunities for this role. The leaders also recognized the increased need for specialized training and how adult learning principles along with integration of new creative digital tools could help enhance engagement, performance and career growth. This article formalizes these learnings, providing best practices for MSLs in the context of the ongoing pandemic and beyond.

INTRODUCTION

MSLs represent a core function of Medical Affairs, acting as the medical face of the organization to provide deep sub-specialty knowledge to healthcare providers and other external stakeholders. MSLs’ primary responsibility focuses on the three pillars of Medical Affairs, i.e. Scientific Exchange, Evidence Generation, and Evidence Dissemination. As such, a primary function of the MSL role is to build and execute an engagement plan in an expanding thought-leadership network. Currently, both the development of these plans and the actions that allow MSLs to deliver on their promise are undergoing sea change.

Over the last decade, healthcare delivery has undergone sweeping reforms. Emerging trends now focus on substantially better cost, quality, and outcomes as the new parameters to demonstrate significant healthcare value. Patients are now at the center of making their healthcare decisions and are demanding data transparency, easy/convenient access, and personalized products and services. Increased need for data transparency and availability has given rise to disruptive technologies and technological advances in the form of advanced data analytics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, digitization, new social media platforms, etc. Alongside these societal and cultural changes, stricter regulations and adjustments to healthcare policy (e.g. changing insurance landscape, use of Real World Evidence, new European Union (EU) regulations, increased scrutiny on drug pricing and rebates, etc.) are driving new ways of thought and action in the healthcare landscape. Meanwhile, the promise of new technologies driving basic and translational research have led Pharmaceuticals and MedTech industries to renew their focus on R&D and scientific advances, leading to personalized medicine breakthroughs in drug-device combinations, small molecule therapeutics, biologics, immunotherapy and diagnostic biomarkers, regenerative medicine and many more areas of advancement in the life sciences industry.

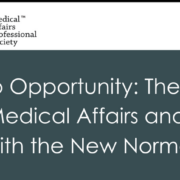

With these dynamic changes taking place in the healthcare landscape, the traditional role of an MSL as a bridge between internal company stakeholders and the outside medical community now needs to expand to encompass new competitive skillsets focusing broadly on Products, People, Personal & Platforms (“4Ps”). The following description of these 4Ps is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather is an attempt to start a new conversation about these core areas to better equip MSLs with a forward-looking understanding of the skill sets needed to succeed in the current and future disrupted healthcare landscape.