Storytelling: The Underappreciated Cornerstone of Evidence-Based Medical Communications

Stephen Towers, PhD

SVP, Medical Affairs Strategy & Transformation, HCG

What is storytelling, and why is it important for Medical Affairs?

The ever-increasing pressure on Medical Affairs organizations to demonstrate the impact of their activities has spawned unprecedented efforts to develop content and programs that are likely to be effective and to deliver a return on investment. This new era of evidence-based medical communications manifests most obviously in data-backed efforts to (1) address the knowledge needs of different audiences (with a reach goal of individual HCP-level personalization), (2) provide content in formats and via channels aligned to audience preferences, and (3) leverage principles of adult learning where possible. However, a major piece of the puzzle that’s often missing is storytelling—namely, the extent to which a narrative style is deployed and the effectiveness of the resulting narratives. “Not storytelling,” you may insist. “Isn’t that one of the most omnipresent buzzwords of our age?” We agree that storytelling has become something of a “bumper sticker.” But how often in the world of pharmaceutical industry-developed medical communications is there anything of substance behind the bumper sticker? Like a bumper. Or even a fully intact car to transport you to another destination, as good storytelling should? In short, and to borrow from the most legendary of storytellers, Hans Christian Andersen, is it possible that the emperor has no…narratives?

A true evidence-based approach to medical communications must give more than lip service to storytelling because it’s associated with numerous benefits over more expository styles of communication for education and knowledge transfer.1-3 A wealth of data indicates that we are neurologically predisposed to focus on content presented in a story format.4 Given the immense volume of new data, the limited time that HCPs have to keep up with new information and the soaring complexity of medical science (novel therapeutic modalities, complex patient journeys, etc), isn’t it time to remind ourselves that HCPs are humans too and provide them—and their patients—with content crafted in a narrative style that resonates on a human level?

Which properties make a story effective?

Imagine a scenario in which we developed educational content for an HCP that aligned with her clinical interests, was packaged into an appealing format (eg, animated video), and was delivered via one of her preferred channels, but it contained a subpar story? It should be obvious that all the exciting technologies, striking visuals, or novel formats in the world won’t rescue a story that’s poorly constructed, ill conceived, lacking in credibility, or boring. So, how can we develop effective stories in Medical Affairs? Before answering that question, we must define what we mean by “effective”—essentially, what do we want our stories to achieve? An effective story is often considered to be one that is:

- attention-grabbing: commanding (and retaining) the attentional focus of the audience5,6

- comprehensible: the ability to be easily understood and to facilitate comprehension of complex concepts3

- engaging: in which the audience feels immersed in, almost experiencing the story—a property often referred to as “narrative transportation”7,8

- persuasive: the power to shape, change, or reinforce the beliefs and possibly also the actions of the audience9

- memorable: easy to recall, resulting in an enduring rather than an ephemeral impact3

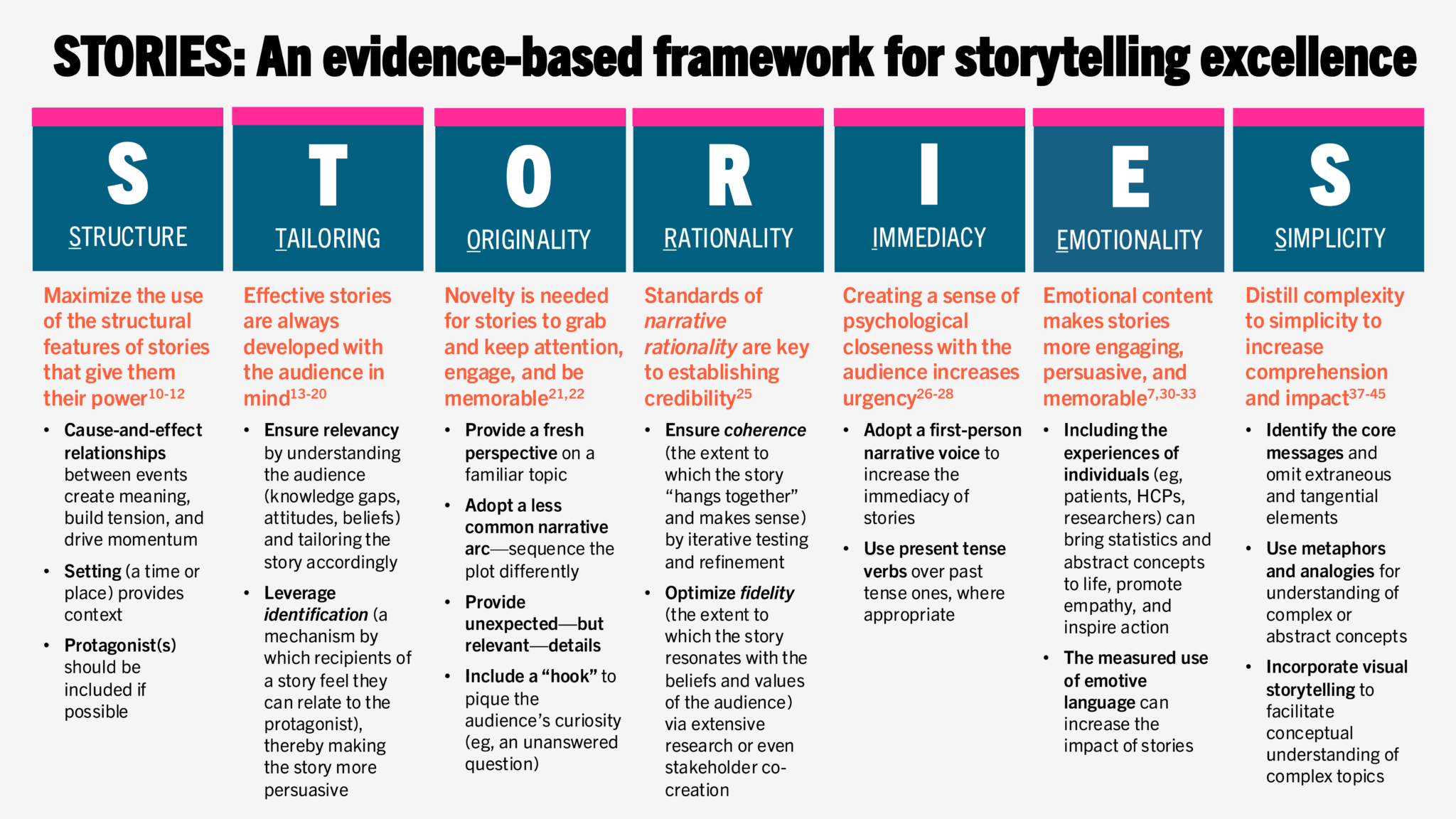

Obviously, these goals are heavily interconnected and interdependent. If your story falls at the first hurdle (grabbing attention), it’s clearly game over for everything else. Importantly, research also indicates that narratives are stripped of their power to persuade and be remembered if the audience is not sufficiently engaged.7 To craft a story that achieves some or all these goals, we can tap into a large and growing body of research, with an evidence base that draws from diverse disciplines, including psychology, linguistics, sociology, pedagogy, and cognitive science. As a proponent of evidence-based medical communications, our team of scientists and narrative experts has reviewed data from across those disciplines to create a simple framework for Medical Affairs storytelling excellence that includes seven key considerations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. STORIES: An evidence-based framework for storytelling excellence includes seven key considerations for effective, purpose-driven stories.

- STRUCTURE. We can view the potential effectiveness of a story by examining how closely its structure resembles that of a typical narrative and the extent to which it contains key elements of stories, including a protagonist, a plot (the series of events in which the protagonist pursues a goal, encounters obstacles, and finds a solution to those obstacles), and a setting (eg, time or location).10,11 These narrative elements and most Medical Affairs topics may seem, prima facie, to be strange bedfellows; for example, does the mechanism of action (MOA) narrative for a new therapy really have a protagonist? With a more expansive mindset, however, perhaps the protagonist could be the molecule itself or even the team of researchers taking the molecule from early-stage R&D to approval and beyond, surmounting numerous obstacles along the way. Another critical and differentiating element of stories is causality—ie, cause-and-effect relationships between events—because it is those that give stories meaning.12 Causality helps the audience to understand the plot and engage with the characters, and it creates momentum for the story.

- TAILORING. Obviously, effective stories are created with the needs of the audience in mind, and a deep understanding of the audience is essential to creating a story that is relevant and will resonate with them. In addition to understanding what audiences know, want to know, and need to know, we must appreciate how their existing attitudes and beliefs could shape their response to the story.13 For HCPs, this includes consideration of the nuances of their specialty, clinical practice setting, demographic and career characteristics (eg, geographic location, number of years in practice), and also their values, attitudes, ethics, and mindset with respect to the topic being communicated. For patient and caregiver stories, we must be mindful that some recipients will have a relatively low level of scientific literacy and a need for a simple story, whereas others will prefer to receive quite detailed information on the disease area or therapy.14 Obtaining a detailed knowledge of our audiences also allows us to leverage a technique known as identification, in which the recipient of a story either believes they have something in common with the protagonist and feels a sense of connection with them (identification through sympathy) or believes they are unlike the protagonist (identification through antithesis).15,16 Research has shown that stories that elicit identification are more likely to engage and persuade the audience.17,18 Finally, a deep knowledge of the target audience is necessary to fully realize one of the major benefits of using stories in healthcare—namely, their ability to reach culturally diverse and marginalized patient populations.19 Our stories will simply fail to resonate with those audiences if they’re lacking in cultural relevance and context.20

- ORIGINALITY. As communicators, we need to recognize we’re in an arms race for the attention of our target audiences. And the battle for hearts and minds starts with a skirmish for attention. The simplest way to grab someone’s attention—and keep it—is to break a pattern; in other words, do something novel or original. This is necessary because we’ve all been exposed to countless narratives (everything from superhero movies to mattress commercials to disease unmet need narratives) over the course of our lives, and the memory of those narratives (stored in semantic knowledge structures known as schemas) sets up expectations for all future stories we encounter.21 Stories that depart from what’s expected (schema incongruent) are more likely to grab attention and are thought to trigger a deeper level of cognitive processing, thereby increasing the engagement of the audience (ie, narrative transportation).22 For ways to achieve schema incongruity in Medical Affairs narratives, we recommend exploring how to tell the story with a fresh perspective, structure the plot differently, include unexpected details, or use a less common narrative arc. When we design storytelling skills training sessions for our clients, we like to emphasize that even relatively minor alterations can make their stories more effective. A good example of this can be seen in the abstracts of peer-reviewed journal articles. A quick PubMed search for review articles on therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy will uncover many abstracts that begin in an almost identical way, with the first sentence being a simple definition of the disease and its burden (eg, “Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe, progressive, muscle-wasting disease, characterized by progressive deterioration of skeletal muscle that causes rapid loss of mobility.”).23 One abstract, however, begins very differently: “Despite the full cloning of the Dystrophin cDNA 35 years ago, no effective treatment exists for the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) patients who have a mutation in this gene.”24 This grabs our attention because it breaks a pattern. It also communicates with urgency by delivering a “call to action”—almost 4 decades and still no effective treatment!

- RATIONALITY. HCPs can detect irrelevant or inauthentic content from a mile away. For that reason, our stories must meet standards of what’s known as narrative rationality, which includes two concepts: coherence and fidelity.25 Coherence is the degree to which the story “hangs together” and makes sense. We need to ask ourselves, “Does this story make sense?” and “How probable is it?” and “Are the characters consistent in their actions?” The second concept, fidelity, is the degree to which the story resonates with the beliefs and values of the audience. Does it “ring true” and match their beliefs and prior experiences? Deep research into the attitudes, experiences, and current knowledge of the target audience is one way to increase the likelihood that it will have fidelity, and stories should also be tested with members of the target audience. However, in our experience, the best way to create an authentic, clinically relevant, and coherent story is to involve members of the target audience—HCP, patient, or patient advocacy group—from the very beginning and co-create the story with them.

- IMMEDIACY. Immediacy is the degree to which there is a psychological sense of closeness or distance between the protagonist and the recipient of a story. One of the most effective ways to increase the immediacy of a story is to use (where appropriate) a first-person narrative voice. First-person voices have been reported to increase the persuasive impact of some health promotion narratives (eg, smoking prevention) compared with narratives that use a third-person voice, an effect that may be due to the first-person voice being more likely to trigger identification with the protagonist.26 First-person pronouns and active verbs can also increase the clarity of writing and may imply greater ownership of the results of a research study, which is why even scientific and medical journals have moved away from insisting that authors use a detached narrative voice in recent years.27 Another linguistic trick that can increase both the immediacy and the impact of narratives is to use present tense verbs over past tense ones, where appropriate.28

- EMOTIONALITY. Research has shown that emotion plays a major role in decision-making.29 For better or worse, emotions may be the main driver of most meaningful decisions in our lives. However, historically, there has been tension between the use of emotion vs rationality in the communication of science. Yet, research has shown that emotional content is effective at commanding attention, engaging and persuading audiences, and making stories more memorable.7,30-33 Including the experiences of individuals (eg, patients, HCPs, researchers) can bring statistics and abstract concepts to life, promote empathy, and inspire action. It’s also been suggested, by our own research and that of others, that the use of emotionally salient language may increase the influence of journal articles.34,35 Anyone wishing to use stories as vehicles for knowledge diffusion should also be aware of the finding that scientific discoveries are more likely to be shared on social media by non-experts if they are framed in a more emotional way.36

- SIMPLICITY. While most effective narratives will require a certain amount of detail and nuance to engage their audiences, the limited capacity of our working memory implies that overly complex or detailed stories could cause saturation, leading to impaired storage in long-term memory of the information we’re trying to impart.37,38 For this reason, our goal should be to create simple stories that are less likely to cause cognitive overload. Simple does not, however, equate to simplistic or “dumbed down.” Rather, it means identifying the core messages we wish to convey, and filtering out extraneous information, tangential elements, and unnecessary details, to leave us with stories that are elegant and intuitive. Because the extent of information processing (the “cognitive load”) imposed by our stories is influenced by prior knowledge of the topic, it’s also necessary to appreciate the audience’s existing level of understanding and tailor the narrative accordingly.39 An additional priority to reduce cognitive load is to connect any new, complex, or abstract concepts in our stories to prior knowledge that the audience has or to familiar, concrete concepts.40 This can be done using metaphors and analogies, and also through visual representations of the content, which enable audiences to convert abstract concepts into specific visual objects.41-43 The effectiveness of visual storytelling—the narrative use of images, videos, and other visual elements—to improve conceptual understanding of complex scientific topics is supported by the dual-coding theory, which proposes that our brains process both verbal and visual representations simultaneously.44,45 The emergence of new formats and technologies— including augmented reality (AR)—enables the creation of ever-more interactive and immersive narrative experiences, with the potential to facilitate a deeper understanding of complex scientific concepts.46

We’ll now examine how some of the key considerations from our evidence-based framework have been practically applied to create stories for diverse Medical Affairs external audiences.

Storytelling for patient and caregiver audiences

According to the MAPS white paper, “The Future of Medical Affairs 2030,” Medical Affairs will increasingly “own the scientific aspects of patient engagement.”47 Yet the task of adequately equipping patients and caregivers with an understanding of their disease and empowering them to actively participate in shared decision-making is no small feat. The three major challenges are low (albeit varying) degrees of scientific literacy in the population at large, the increasing complexity of novel therapies, and the often-suboptimal nature of HCP–patient communications. Regarding the latter, it’s not uncommon that even HCPs with a solid grasp of the science can struggle to educate or counsel their patients on complex concepts.48-50 Perhaps it’s not surprising then that the content HCPs value most from pharmaceutical companies—according to several surveys —is medical content they can use with their patients.51,52 Thankfully, there’s considerable evidence to indicate that content provided in a narrative form can be particularly effective for patient and caregiver audiences, including for communicating and contextualizing risk, changing health behaviors, and fostering empathy and understanding of patients among providers.53-56

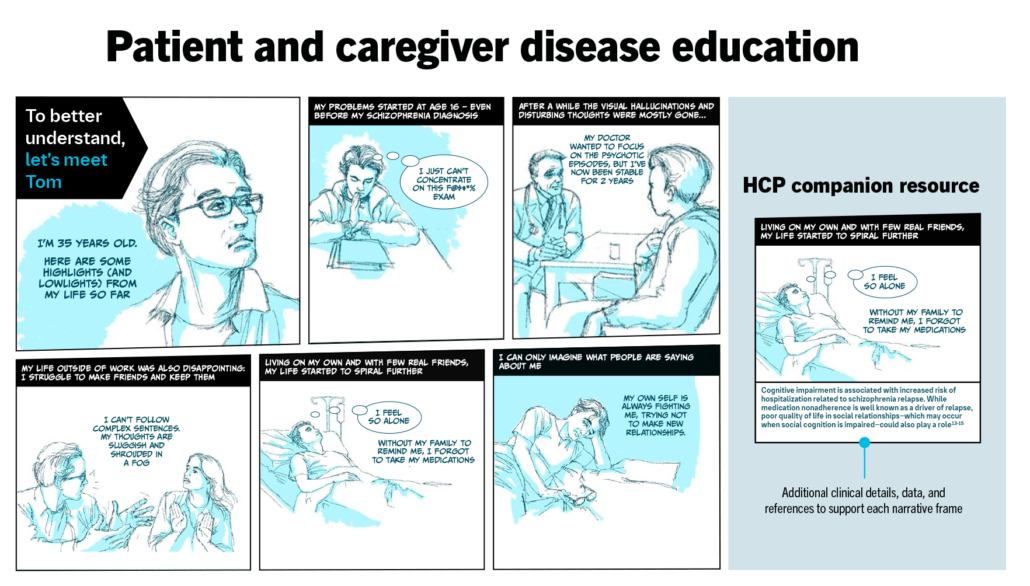

Shown in Figure 2 is an example of a graphic novel–style patient journey story we created to educate patients with cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia (CIAS) and their caregivers about the illness. The aim of this resource was to make patients feel “seen” and counter the internalized stigma that may prevent them from mentioning to their HCPs how severely they are impacted by the cognitive symptoms. To achieve this, we created the life story of a fictional patient named Tom—based on a composite of several patients’ experiences. This format was designed to leverage the storytelling technique of identification, mentioned earlier, to increase the engagement of our target audience. A companion version of Tom’s story was created for HCPs, with additional clinical details, data, and references to support each narrative frame. With this version, our goal was to increase HCPs’ empathy and understanding of the burden that cognitive impairment imposes on so many aspects of their patients’ lives, thereby encouraging person-centered care. Though graphic novels are a relatively new medical communications format, they have already shown promise in a number of patient, caregiver, and HCP use cases.57-59

Figure 2. Innovative, graphic novel–style disease education resource to educate patients and caregivers (TAILORING, RATIONALITY, EMOTIONALITY)

Storytelling to translate complex science for HCPs

Creating a simple, clinically meaningful mechanism of disease story or MOA story for a novel therapy is not easy. This is partly due to the immense complexity of biological pathways and processes, but it’s also because many of the newer therapeutic modalities (eg, cell and gene therapies, antibody-drug conjugates, prescription digital therapeutics) are truly innovative, but not always intuitive. Another enemy of a simple story that’s all too common is a state of uncertainty, such as an incomplete or evolving understanding of the science.60 Perhaps the most significant challenge we face, however, is that human cognition has evolved in a way that biases us toward understanding “human-scale” objects that can be easily observed (eg, a tree), rather than micro- or nanoscale objects (eg, a 150-nm virus) or cosmic-scale objects (eg, black holes).61

One response to these challenges within a narrative is to deploy metaphors or similes.62 Metaphors can create powerful mental images that provide a frame of reference for an abstract or unfamiliar concept by bridging it to the concrete or familiar.63 Metaphors are ubiquitous in science for making complex concepts more accessible, and they’re frequently used in HCP–patient conversations. Indeed, one study found that oncologists include, on average, at least one metaphor in each conversation they have with patients who have advanced cancer.64

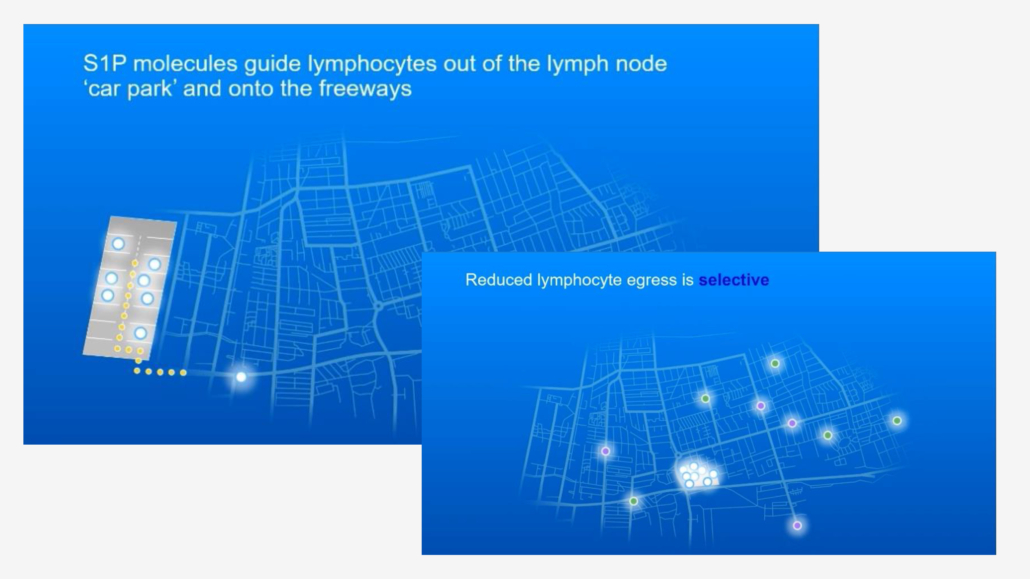

A recent project to create a clinically meaningful MOA narrative for an ulcerative colitis therapy provides a good example. The immunology underlying chronic inflammatory diseases is complex, but we wanted to make the MOA narrative accessible, memorable, and relatable. The therapy acts by reducing the trafficking of some specific types of immune cells to the site of inflammation. We partnered with our clients to develop a simple metaphor that likened cell trafficking in ulcerative colitis to vehicle traffic in a complex urban environment; consider the cells as cars, each on a journey to a specific destination, analogous to immune cells travelling around the body to sites of inflammation, injury, or infection (Figure 3). This metaphor was used to illustrate the healthy state, untreated disease, and the impact of the new therapy on reducing traffic to inflamed sites, while retaining the ability to respond rapidly to infection or injury.

Figure 3. Visual storytelling and metaphors to translate complex science: Pfizer symposium at the 18th Congress of European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO), March 1-4, 2023 (ORIGINALITY, SIMPLICITY)

Storytelling to improve HCP skills and clinical practice

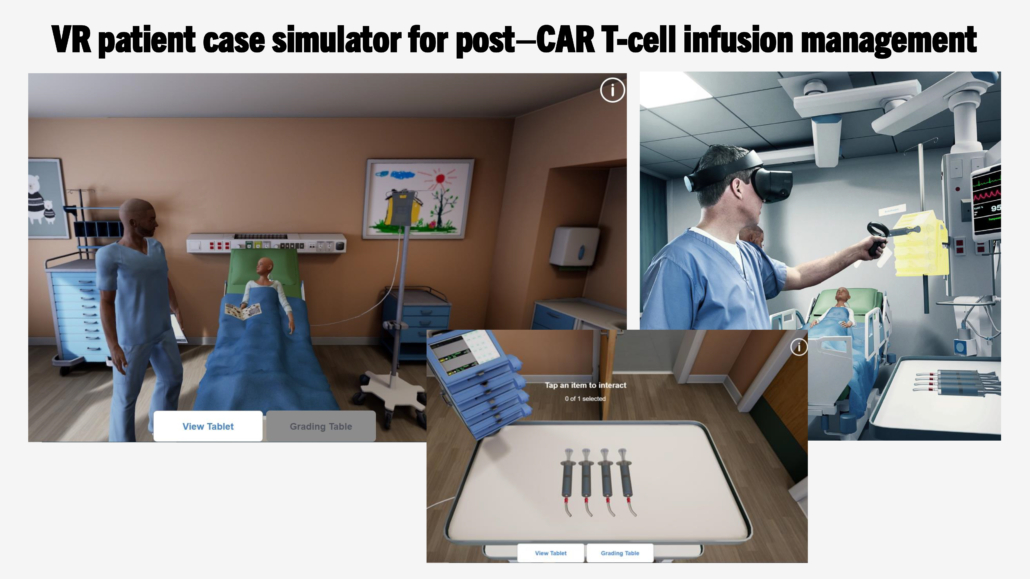

New technologies, such as virtual reality (VR), offer the potential for storytelling of an even greater intensity. With the ability to create 3D simulations of real-world objects, locations, and interactions, VR has already demonstrated significant potential for medical education, clinical skills training (eg, surgical training), and role-playing.65 We recently developed a VR patient case study simulator to educate physicians on post-infusion side effects of CAR T-cell therapy and equip them with the skills to manage them effectively (Figure 4). Up to 93% of patients with relapsing/remitting diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can experience cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic side effects that require urgent and complex care following CAR T infusion. Through an immersive, real-time experience, we recreated the high-pressure, time-sensitive clinical environment in which treating physicians can hone their skills by reviewing patients’ medical history, monitoring patient vitals, and using treatment tools and consensus guidelines to make real-time clinical decisions. At the heart of the experience were four distinct patient stories—two pediatric and two adult patients of varying CRS and neurotoxicity severity. We leveraged storytelling principles of tailoring and emotionality with the CAR T VR tool—the emotionality came from insights that the audience were reluctant to prescribe CAR T therapies based on a fear of how to manage the potential serious side effects of the early CAR Ts, and the tailoring came from how we designed it as an in-clinic experience and modelled the characters on the actual staff who would be involved in the delivery of care.

Figure 4. Immersive storytelling for HCP skills training: VR patient case simulator for post–CAR T-cell infusion management (TAILORING, EMOTIONALITY)

What does the future hold for storytelling?

In the coming years, storytelling will become more interactive and immersive (shaped by extended reality [XR] technologies and AI), more personalized and participatory, and more collaborative. The basic properties that give stories their power will endure, but there will be a need for ongoing exploration and research into how each new medium and technology can be exploited to create and deliver the most effective stories for our audiences. Though the pace of change may seem daunting, Medical Affairs professionals should feel reassured that any time spent honing their narrative skills will ultimately lead to more effective engagement of a broader range of stakeholder groups, thereby equipping them for success as the role of Medical Affairs within the industry and society evolves.

References

- Brooks SP, Zimmermann GL, Lang M, et al. A framework to guide storytelling as a knowledge translation intervention for health-promoting behaviour change. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):35.

- Braddock K, Dillard JP. Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs. 2016;83(4):446-467.

- Mar RA, Li J, Nguyen ATP, Ta CP. Memory and comprehension of narrative versus expository texts: a meta-analysis. Psychon Bull Rev. 2021;28(3):732-749.

- Nguyen M, Vanderwal T, Hasson U. Shared understanding of narratives is correlated with shared neural responses. NeuroImage. 2019;184:161-170.

- Song H, Finn ES, Rosenberg MD. Neural signatures of attentional engagement during narratives and its consequences for event memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(33):e2021905118.

- Gordon R, Ciorciari J, van Laer T. Using EEG to examine the role of attention, working memory, emotion, and imagination in narrative transportation. European Journal of Marketing. 2018;52(1/2):92-117.

- Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(5):701-721.

- Busselle R, Bilandzic H. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychology. 2009;12(4):321-347.

- Bullock OM, Shulman HC, Huskey R. Narratives are persuasive because they are easier to understand: examining processing fluency as a mechanism of narrative persuasion. Frontiers in Communication. 2021;6.

- Freytag G, MacEwan EJ. Freytag’s Technique of the Drama. Scholarly Press; 1894.

- Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Varieties of Narrative Analysis. Sage; 2012.

- Chen J, Bornstein AM. The causal structure and computational value of narratives. Trends Cogn Sci. 2024;28(8):769-781.

- Shen F, Ahern L, Han J. Environmental orientations and news coverage: Examining the impact of individual differences and narrative news. International Journal of Communication. 2017;11:14.

- Desine S, Hollister BM, Abdallah KE, Persaud A, Hull SC, Bonham VL. The meaning of informed consent: genome editing clinical trials for sickle cell disease. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2020;11(4):195-207.

- Burke K. The Rhetorical Situation. In: Communication: Ethical and Moral Issues. Gordon and Breach; 1973:263-275.

- Cohen J. Defining identification: a theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication and Society. 2001;4(3):245-264.

- Oschatz C, Emde-Lachmund K, Klimmt C. The persuasive effect of journalistic storytelling: experiments on the portrayal of exemplars in the news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2019;98(2):107769901985009.

- Phelps A, Rodriguez-Hernandez Y, Murphy ST, Valente TW. A culturally tailored narrative decreased resistance to COVID-19 vaccination among Latinas. Am J Health Promot. 2023;37(3):381-385.

- Singh JA, Joseph A, Baker J, et al. SToRytelling to Improve Disease outcomes in Gout (STRIDE-GO): a multicenter, randomized controlled trial in African American veterans with gout. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):265.

- Myers KR, Green MJ. Storytelling: a novel intervention for hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):129-130.

- DeRosia ED, Lee TR, Christensen GL. Sophisticated but confused: the impact of brand extension and motivation on source confusion. Psychology and Marketing. 2011;28(5):457-478.

- Houghton DM. Story elements, narrative transportation, and schema incongruity: a framework for enhancing brand storytelling effectiveness. Journal of Strategic Marketing. 2021;31(7):1263-1278.

- Chang M, Cai Y, Gao Z, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: pathogenesis and promising therapies. J Neurol. 2023;270(8):3733-3749.

- Heydemann A, Siemionow M. A brief review of Duchenne muscular dystrophy treatment options, with an emphasis on two novel strategies. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):830.

- Fisher WR. The narrative paradigm: an elaboration. Communication Monographs. 1985;52(4):347-367.

- Igartua J, Rodríguez-Contreras L. Narrative voice matters! Improving smoking prevention with testimonial messages through identification and cognitive processes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7281.

- Hyland K. Options of identity in academic writing. ELT Journal. 2002;56(4):351-358.

- Guizzardi S, Colangelo MT, Mirandola P, Galli C. Tracing the evolution of reviews and research articles in the biomedical literature: a multi-dimensional analysis of abstracts. Publications. 2024;12:2.

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Role of the amygdala in decision-making. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:356-369.

- Barraza JA, Alexander V, Beavin LE, Terris ET, Zak PJ. The heart of the story: peripheral physiology during narrative exposure predicts charitable giving. Biol Psychol. 2015;105:138-143.

- Zak PJ. Why inspiring stories make us react: the neuroscience of narrative. Cerebrum. 2015;2015:2.

- Zak PJ, Stanton AA, Ahmadi S. Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. PLoS One. 2007;2(11):e1128.

- Morris BS, Chrysochou P, Christensen JD, et al. Stories vs. facts: triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change. Climatic Change. 2019;154(1-2):19-36.

- Towers SK, Turan Z, Spataro K. Using storytelling to communicate complex science: a quantitative and qualitative assessment of the narrative properties of journal articles on genetic medicines. Original Abstracts from the 20th Annual Meeting of ISMPP. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(sup2):5-40.

- Hillier A, Kelly RP, Klinger T. Narrative style influences citation frequency in climate change science. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167983.

- Milkman KL, Berger J. The science of sharing and the sharing of science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):13642-13649.

- Sweller J. Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2020;68(1):1-16.

- Paas F, van Gog T, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory: new conceptualizations, specifications, and integrated research perspectives. Educational Psychology Review. 2010;22(2):115-121.

- Tobler S, Sinha T, Koehler K, Hafen E, Kapur M. The impact of prior knowledge in narrative-based learning on understanding biological concepts in higher education. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society; 2022:44(44). doi:10.3929/ethz-b-000553260

- Belenky DM, Schalk L. The effects of idealized and grounded materials on learning, transfer, and interest: an organizing framework for categorizing external knowledge representations. Educational Psychology Review. 2014;26(1):27-50.

- Holyoak KJ, Stamenković D. Metaphor comprehension: a critical review of theories and evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2018;144(6):641-671.

- Evagorou M, Erduran S, Mäntylä T. The role of visual representations in scientific practices: from conceptual understanding and knowledge generation to “seeing” how science works. International Journal of STEM Education. 2015;2(1):11.

- McClean P, Johnson C, Rogers R, et al. Molecular and cellular biology animations: development and impact on student learning. Cell Biology Education. 2005;4(2):169-179.

- Paivio A, Clark J. Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review. 1991;3(3):149-210.

- Mayer RE. The past, present, and future of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. Educational Psychology Review. 2024;36(1).

- Marques AB, Branco V, Costa R. Narrative visualization with augmented reality. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2022;6(12):105.

- Medical Affairs Professional Society (MAPS). The Future of Medical Affairs 2030. 2022.

- Oreja-Guevara C, Potra S, Bauer B, et al. Joint healthcare professional and patient development of communication tools to improve the standard of MS care. Adv Ther. 2019;36(11):3238-3252.

- Children and Young People’s Survey 2020—Care Quality Commission. [(accessed on December 19, 2024)]. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/children-young-peoples-survey-2020.

- van Dulmen S, Roodbeen R, Schulze L, et al. Practices and perspectives of patients and healthcare professionals on shared decision-making in nephrology. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):258.

- Physician Learning Preferences: A Doximity Report. October 2022.

- The New Rules of Engagement. Accenture Report, 2021.

- Shanahan EA, Reinhold AM, Raile ED, et al. Characters matter: how narratives shape affective responses to risk communication. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225968.

- Houston TK, Cherrington A, Coley HL, et al. The art and science of patient storytelling-harnessing narrative communication for behavioral interventions: the ACCE project. J Health Commun. 2011;16(7):686-697.

- Jackson LE, Saag KG, Chiriboga G, et al. A multi-step approach to develop a “storytelling” intervention to improve patient gout knowledge and improve outpatient follow-up. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101149.

- Auld K, Devaparanam I, Roberts S, McInerney J. Lived experiences of healthcare. Putting the person in person centred care in the medical radiation sciences. Radiography (Lond). 2024;30(3):856-861.

- Sutherland T, Choi D, Yu C. “Brought to life through imagery” – animated graphic novels to promote empathic, patient-centred care in postgraduate medical learners. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):66.

- Haan MM, van Gurp JL, Knippenberg M, Olthuis G. Facilitators and barriers in using comics to support family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care at home: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2022;36(6):994-1005.

- Dean M, Boumis JK, Zhong L, et al. Assessing the acceptability and appropriateness of a psychoeducational graphic novel about inherited cancer risk designed for men. J Genet Couns. Published online August 7, 2024.

- Fischhoff B, Davis AL. Communicating scientific uncertainty. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(Supplement 4):13664-13671.

- Dahlstrom MF, Ritland R. The problem of communicating beyond human scale. In: J Goodwin (ed), Between scientists & citizens: Proceedings of a conference at Iowa State University. Great Plains Society for the Study of Argumentation; 2012:121-130.

- Dahlstrom MF. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):13614-13620.

- Ten Have H, Gordijn B. Metaphors in medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 2022;25(4):577-578.

- Casarett D, Pickard A, Fishman JM, et al. Can metaphors and analogies improve communication with seriously ill patients?. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(3):255-260.

- Liu JYW, Yin YH, Kor PPK, et al. The effects of immersive virtual reality applications on enhancing the learning outcomes of undergraduate health care students: systematic review with meta-synthesis. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e39989.