Authors

This publication represents the consensus opinions of the authors and various members of MAPS but does not represent formal endorsement of the conclusions by their organizations

Karen King

Sarah Yelling

Simon Stones

Dheepa Chari

ABSTRACT

A plain-language summary (PLS) can play a key role in communicating clinical research more broadly to patients. There are two types of PLSs, a clinical trial summary (CTS), which is mandated by law on clinical trial databases, and a publication PLS, which summarizes the results of a publication (abstract or manuscript) in plain language. A CTS is templated with narrow scope and is aimed primarily for clinical trial participants.

A PLS is intended for a wider audience (patients, caregivers, public, media, and some healthcare providers [HCPs]), has a broader scope, and is generated in a wide variety of formats. Some pharmaceutical companies have raised concerns around the potential for PLS to be considered promotional activity; therefore, we provide some clear practical recommendations to overcome this perceived barrier, as well as tips to optimize development and accessibility. More should be done to inform patients of emerging clinical research and the development of CTSs and PLSs can help facilitate these efforts.

INTRODUCTION

While literacy is the ability to read and write, health literacy is all that and more, particularly when it is a lay audience of patients, their caregivers, and the general public who must be engaged and educated.

“Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”1

When written content is easy for patients to understand, the benefits are manifold: the relevance of the information is seen immediately and comprehension is better, ultimately meaning that patients can be more involved in the decision-making process. When patients understand benefits and risks in a clear and transparent way, adherence to treatment can be improved and there is reassurance and trust in their healthcare providers (HCPs).

With increasing awareness of the benefits of communicating clinical trial research to patients there has been increased interest in how we can do this in a compliant and non-promotional way. In this article, we outline two key approaches:

- Clinical trial summary (CTS) – mandated by law in certain countries, typically on clinical trial sites, following a templated style with a narrow scope. The primary purpose of a CTS is to inform about the details of the trial itself, particularly for trial participants.

- Publication plain-language summary (PLS) – can be for congress abstracts and manuscripts, located on different sites, and developed in different formats. The primary purpose of a publication PLS is to outline the results of a publication in plain language intended for a wider audience beyond HCPs.

CTS – AN INTERNATIONAL REQUIREMENT

An awareness of health literacy is essential when writing for potential clinical trial participants and crucial when reporting trial results back to patients and caregivers who have directly participated in trials and/or contributed their time and effort. The CTS became a requirement after the advent of the European Union/European Medicines Agency (EU/EMA) guidelines that mandated transparency in reporting clinical trial data to both study participants and the general public.2 A templated framework is part of this directive and ensures that all relevant information is provided to the lay reader in a balanced way. This includes reporting of “adverse reactions” (a statutory term) and study outcomes, both positive and negative. Guidance is also given regarding the harmony between text and graphics to make certain the lay reader remains engaged in the content and understands the scientific data presented.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on CTS development is somewhat less stringent and still in draft format: “This guidance is intended to facilitate the voluntary provision of plain language summaries…”3 It is noted in this draft guidance that the provision of plain-language summaries in the EU is mandatory and the FDA does intend to comply with international regulations. Although in draft format, there is a similar templated framework that offers general considerations on content, ensuring the level of communication is appropriate for the audience, health literacy and numeracy, the timing of the PLS (within one year of the study ending), and appropriate methods of delivery.

ANSWERING YOUR QUESTIONS ON PUBLICATION PLS

As pharmaceutical companies recognize the need to be more patient-centric there has been recent significant interest in publication PLSs from company-sponsored medical research. However, the lack of guidelines and consistency of approach means many questions still remain regarding best practice.

Notably, who are the target audiences for a publication PLS? The primary audiences are undoubtedly the patient or caregiver. If pitched right for them, it will be inclusive of the public and media, as well as non-specialist HCPs or those who lack time.

Although journals do typically offer other “bite-sized” content which may be more valuable to certain HCPs.

One of the challenges faced by pharmaceutical companies sponsoring publication PLS development is ensuring compliance with industry-level scientific exchange best practices. Because the intent in communicating scientific data transparently with patients is to help them understand research developments in a timely and credible manner, our recommendations to tackle this are:

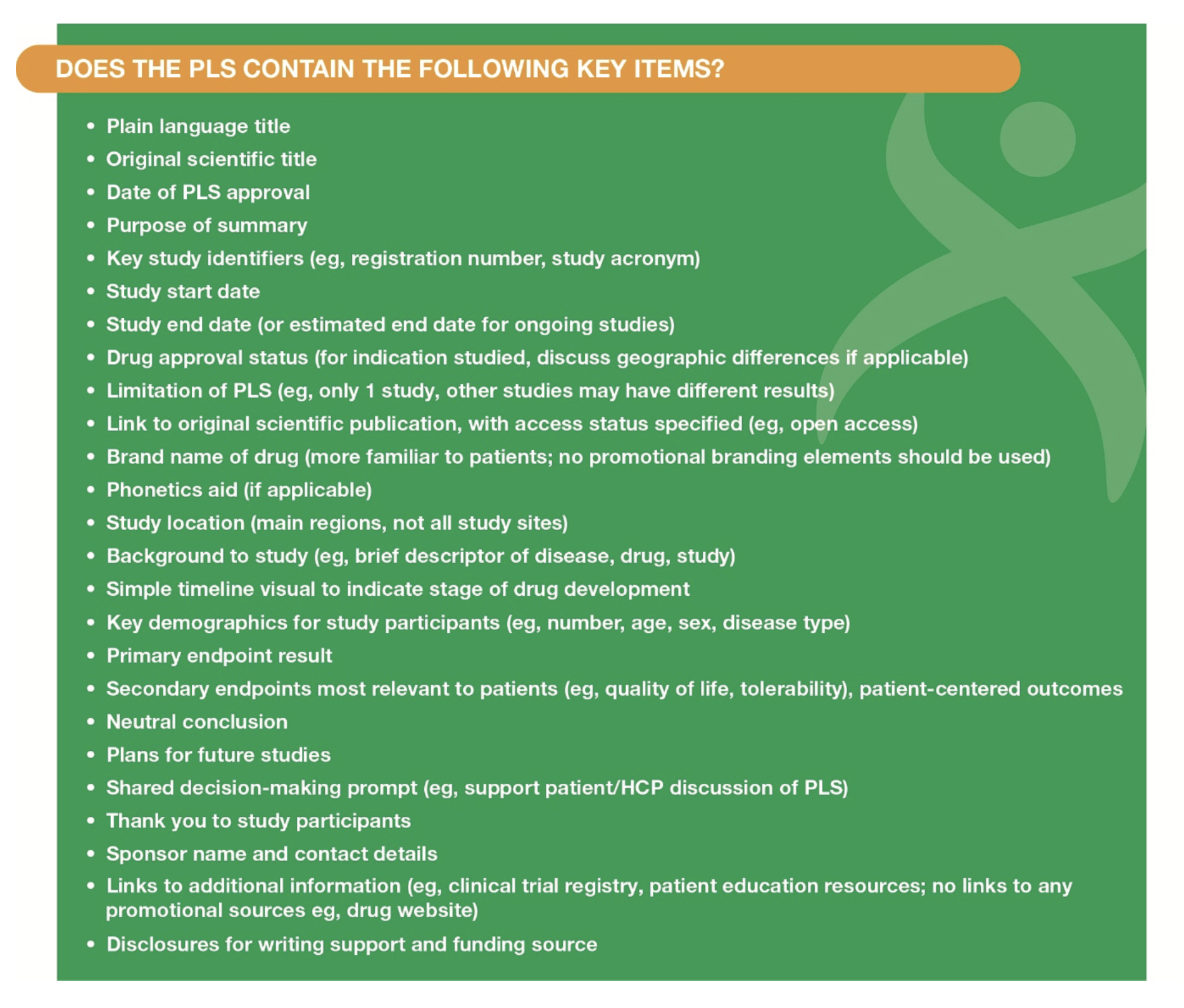

- Publication PLSs should be peer reviewed alongside the original manuscript and the scope should be primarily limited to that of the manuscript or congress abstract. Some additional context to help patients interpret the findings accordingly may be added (e.g., disease area, drug mechanism of action). A checklist for what should be included in a publication PLS is shown in Figure 1.

- To prevent any suggestion of bias by the sponsor, objective criteria should be developed and used consistently for selection of publications for which to include a PLS (e.g., Phase III data is more broadly applicable to a wider audience as it is more likely to imminently impact clinical practice relative to Phase I data).

- PLSs should be planned for from the outset of a publication’s life. Publication planning databases now list journals that accept PLSs. If journal publication of a PLS is not possible there are other options such as hosting on Figshare.com and Kudos.com.

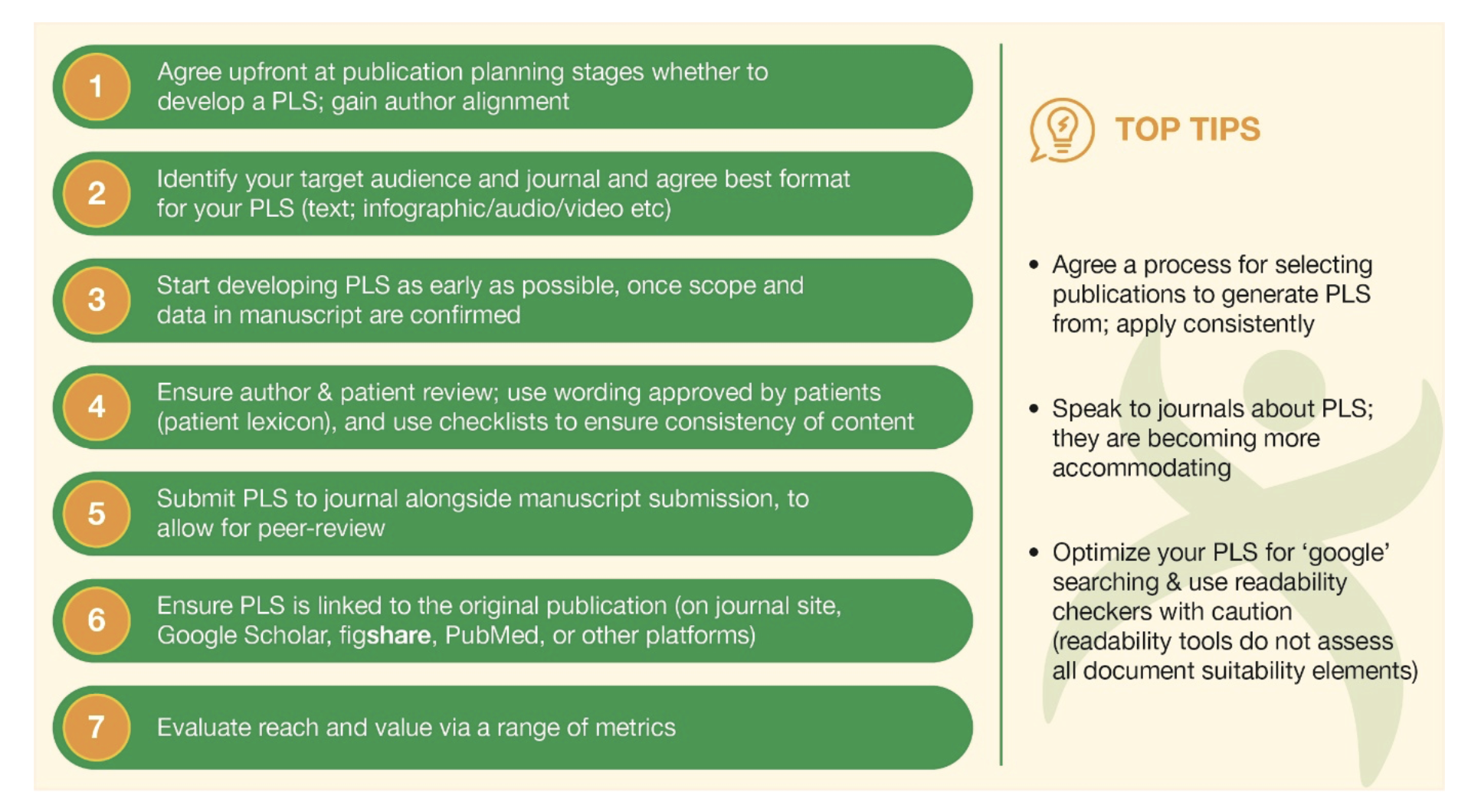

- A defined development process should be used. Some recommendations regarding this process are outlined in Figure 2.

Even if a journal does not currently mention PLS in its author instructions, in our experience, many are open to having discussions about how they can facilitate this option.

A recent research study in partnership with patient advocacy groups (PAGs) examining optimal formats for PLSs suggested a visual infographic style and an optimal reading age of medium complexity.4 Cochrane has also examined the usefulness of different formats for translating the results of a systematic review and found that although there was no difference in knowledge translation between the infographic and text-based PLS formats, they preferred the infographic, giving it higher ratings for reading experience and user-friendliness.5 Therefore, infographic is likely to be the preferred option for people to digest, with text-based being useful for translation; however, other audience-specific points should be considered (such as age, culture, translation needs and accessibility requirements) before format/complexity is decided. Manuals on health literacy can also offer further guidance on this topic.6

Lastly, given that publishers are using different terminology and platforms for hosting the PLSs, how do we ensure that a PLS can reach the target audience? Recent research examining journals from 10 different publishers demonstrated that PLSs are typically outside of the journal paywall, which is a positive first step.7 However, more needs to be done to increase reach, highlighting the importance of planning a good dissemination strategy, such as reaching out to PAGs and medical research charities as they are one of the key vehicles to widening reach with the patient/caregiver community. Other recommendations, such as consistent naming and location, and ensuring that a PLS is search-engine optimized and linked to the original

publication (on journal site or other available platforms) would also help. Although PubMed now indexes PLSs, we would also advocate for a patient-friendly searchable repository – a “PubMed for patients”. Of course, measuring reach and value will be important and these could be assessed by basic download metrics alongside other qualitative measures such as surveys and focus groups.

An initiative led by the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP), McCann Health Medical Communications, and Envision Pharma to more thoroughly understand perspectives on publication PLSs from stakeholders, including patients, media, HCPs, pharma companies, publishers, and medical communication agencies is currently ongoing. We eagerly await their publication to inform future direction for PLSs.

PUTTING IT INTO ACTION: KEY PHARMA AND PATIENT LEARNINGS FROM PFIZER ONCOLOGY

Given the desire for patients to access data at the earliest possible opportunity and the fact that many scientific congresses now have patient tracks, Pfizer Oncology ran a pilot developing abstract PLSs (APLSs) of scientific content at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting in 2018.9 This was the first time that this had been carried out at a major scientific congress.

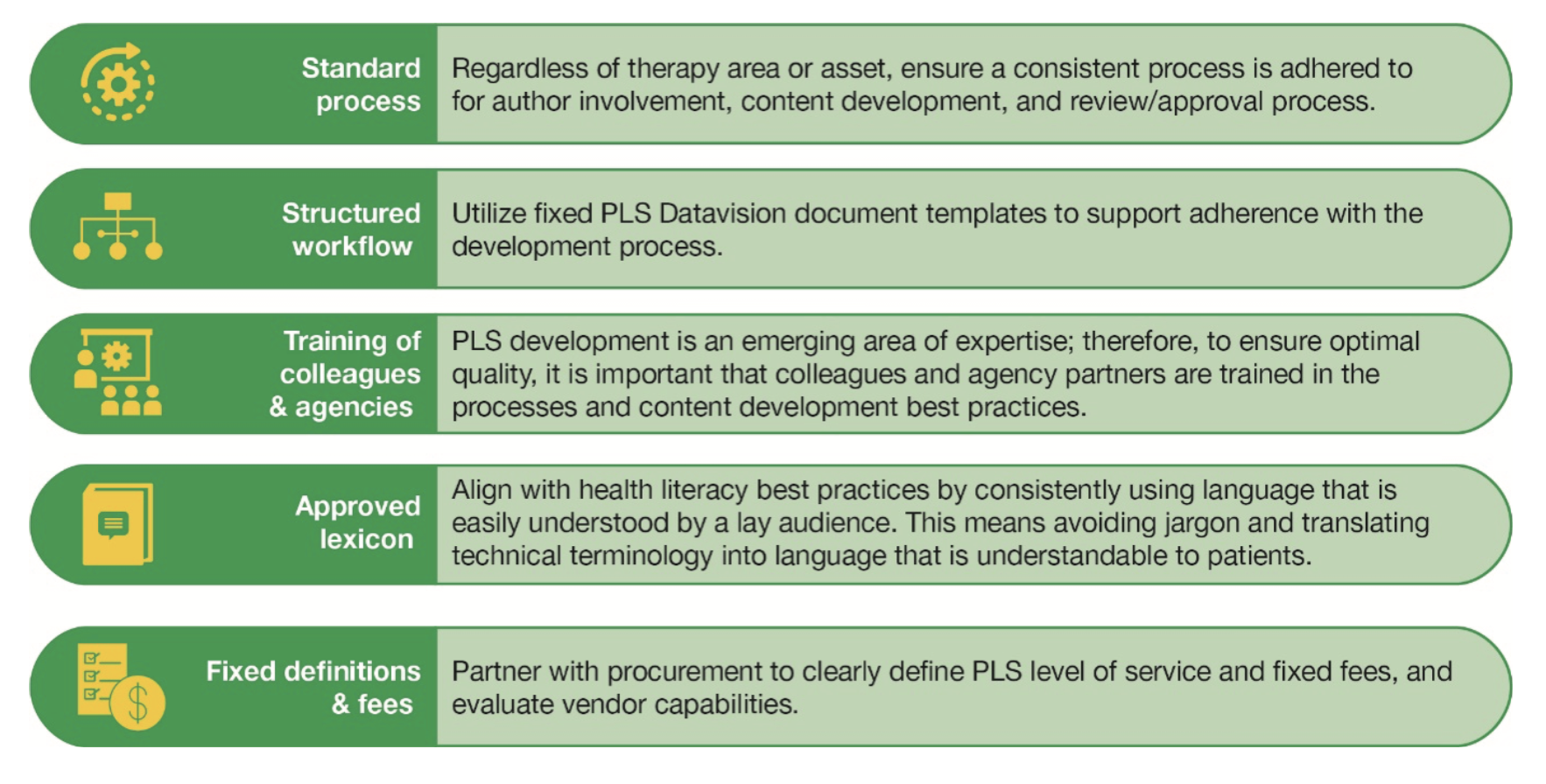

Several challenges were encountered in navigating compliance guardrails around patient-directed communication, which necessitated developing a new governance process that would allow for the APLSs to be written effectively. In addition, internal and external authors needed to be educated on the importance of the initiative, as it would result in added workload related to scientific congresses. The team overcame these obstacles through close collaboration with the medical and clinical teams, lead authors, and patient partners; key learnings are outlined in Figure 3.10

It was important to make certain that any APLS is developed with comprehensible reading-level requirements while ensuring an accurate reflection of the original scientific content. The input of patient partners was critical for developing APLSs that were fit for purpose. Although medical writers trained in writing a PLS are well placed to facilitate their production, the patient voice cannot be overlooked. For example, patients and caregivers, particularly those who aren’t active patient advocates, may require some further information to enable them to interpret the research findings more easily.

An APLS accurately conveys the core messages contained within the accepted abstracts while also providing concise “nuggets” of information about certain types of cancer and certain molecular targets. These points were picked up by patient reviewers involved in the development and “sense checking” of the APLS.

Gone are the days of clinician-only congresses. More and more of these meetings have patient and caregiver streams running in parallel with, and even fully integrated into, the scientific program. Many patient and caregiver advocates and organizations use these congresses as opportunities to gather the latest research findings to report back to their communities online or via standalone meetings. The provision of an abstract and poster PLS thus helps to maintain that continuity of information provision to patients and caregivers in anticipation for final, full-text manuscripts being published. Some industry colleagues have concerns over the interim reporting of findings that have not been formally peer reviewed; therefore, such disclaimers could be included on each PLS to make it clear to readers that the data may not fully reflect those reported in the final results.

CONCLUSION

The entire community must remember that without patients, there would be no industry. It is everyone’s obligation to ensure that patients who participate in research are kept informed through the transparent communication of research findings, whether they are positive or negative in a timely manner. Both CTSs and publication PLSs have key roles to play in this process. Research belongs to us all.

REFERENCES

- Health Literacy – Healthy people 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/heal th-literacy. Accessed 3 November 2020.

- Summaries of clinical trial results for laypersons. Recommendations of the expert group on clinical trials for the implementation of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-10/2017_01_26_summaries_of_ct_results_for_laypers ons.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2020.

- Draft FDA Guidance on Provision of Plain Language Summaries. Issued by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Available at: https://mrctcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-06-13-MRCT-Draft-FDA-Guidance-Return-of-Aggregate- Results.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2020.

- Silvagnoli LM, Gardner J, Shepherd C, Pritchett J. Evaluation of plain-language summaries (PLS): optimising readability and format. Poster presented at ISMPP Annual Meeting 2019.

- Buljan I, Malički M, Wager E, et al. No difference in knowledge obtained from infographic or plain language summary of a Cochrane systematic review: three randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 97: 86–94.

- Optimizing Language Summaries using Health Literacy Best Practices: An Applied Manual (September 30, 2020).

- FitzGibbon H, King K, Piano C, Wilk C, Gaskarth M. Where are biomedical research plain‐language summaries? Health Sci Rep 2020; 3: e175.

- Shepherd C, Fisher G, Beinarovicac J, Gardner J. Could PubMed be a viable route to discovering plain language summaries? Poster presented at ISMPP Annual Meeting 2020.

- Chari D, Arnstein L, Passador L, Biegi T, Stones S, Matthews P, Ward H, Gordon M. Defining a process for developing and disseminating abstract plain language summaries for scientific congresses: a case study. Poster presented at ISMPP EU 2020.

- Sykes A, Chari D, Meloro JR. Developing a company-wide process for publication plain language summaries. Poster presented at ISMPP Annual Meeting 2020.

Figures

Figure 1. Checklist for what to include in a publication PLS, courtesy of Envision Pharma Group.

Figure 2. Proposed process for developing a manuscript publication PLS

Figure 3. Best practices for pharmaceutical companies to adopt when working on a PLS